A John Braheny Songmine column from the archives…

Accession Number: C000000137-022-002 Document/Digital File, “Songmine: For the non-writing artist: Where do you find original material by John Braheny”, OCR converted text under same Accession Number

(Digitally converted text. Some errors may occur)

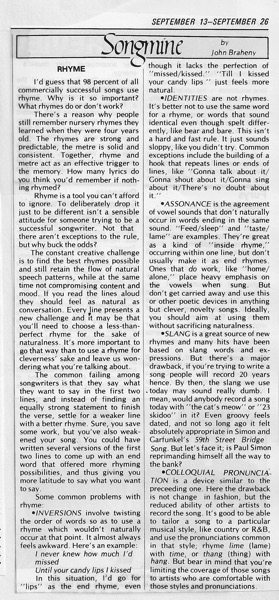

SEPTEMBER 13—SEPTEMBER 26

Songmine by John Braheny

RHYME

I’d guess that 98 percent of all commercially successful songs use rhyme. Why is it so important? What rhymes do or don’t work?

There’s a reason why people still remember nursery rhymes they learned when they were four years old. The rhymes are strong and predictable, the metre is solid and consistent. Together, rhyme and metre act as an effective trigger to the memory. How many lyrics do you think you’d remember if noth-ing rhymed?

Rhyme is a tool you can’t afford to ignore. To deliberately drop it just to be different isn’t a sensible attitude for someone trying to be a successful songwriter. Not that there aren’t exceptions to the rule, but why buck the odds?

The constant creative challenge is to find the best rhymes possible and still retain the flow of natural speech patterns, while at the same time not compromising content and mood. If you read the lines aloud they should feel as natural as conversation. Every line presents a new challenge and it may be that you’ll need to choose a less-than-perfect rhyme for the sake of naturalness. It’s more important to go that way than to use a rhyme for cleverness’ sake and leave us won-dering what you’re talking about.

The common failing among songwriters is that they say what they want to say in the first two lines, and instead of finding an equally strong statement to finish the verse, settle for a weaker line with a better rhyme. Sure, you save some work, but you’ve also weak-ened your song. You could have written several versions of the first two lines to come up with an end word that offered more rhyming possibilities, and thus giving you more latitude to say what you want to say.

Some common problems with rhyme:

•1NVERSIONS involve twisting the order of words so as to use a rhyme which wouldn’t naturally occur at that point. It almost always feels awkward. Here’s an example:

I never knew how much I’d missed

Until your candy lips I kissed

In this situation, I’d go for “lips” as the end rhyme, even though it lacks the perfection of “missed/kissed.” “Till I kissed your candy lips ” just feels more natural.

• IDENTITIES are not rhymes. It’s better not to use the same word for a rhyme, or words that sound identical even though spelt differ-ently, like bear and bare. This isn’t a hard and fast rule. It just sounds sloppy, like you didn’t try. Common exceptions include the building of a hook that repeats lines or ends of lines, like “Gonna talk about it/ Gonna shout about it/Gonna sing about it/There’s no doubt about it.”

• ASSONANCE is the agreement of vowel sounds that don’t naturally occur in words ending in the same sound. “Feed/sleep” and “taste/ lame” are examples. They’re great as a kind of “inside rhyme,” occurring within one line, but don’t usually make it as end rhymes. Ones that do work, like “home/ alone,” place heavy emphasis on the vowels when sung. But don’t get carried away and use this or other poetic devices in anything but clever, novelty songs. Ideally, you should aim at using them without sacrificing naturalness.

•SLANG is a great source of new rhymes and many hits have been based on slang words and ex-pressions. But there’s a major drawback, if you’re trying to write a song people will record 20 years hence. By then, the slang we use today may sound really dumb. I mean, would anybody record a song today with “the cat’s meow” or “23 skidoo” in it? Even groovy _ feels dated, and not so long ago it felt absolutely appropriate in Simon and Garfunkel’s 59th Street Bridge Song. But let’s face it; is Paul Simon reprimanding himself all the way to the bank?

• COLLOQUIAL PRONUNCIATION is a device similar to the preceeding one. Here the drawback is not change in fashion, but the reduced ability of other artists to record the song. It’s good to be able to tailor a song to a particular musical style, like country or R&B, and use the pronunciations common in that style; rhyme lime (lame) with time, or thang (thing) with hang. But bear in mind that you’re limiting the coverage of those songs to artists’ who are comfortable with those styles and pronunciations.

Previously in the Songmine Collection:

- Songmine: “The Knack” A 3rd Point of View by John Braheny

- Songmine: For the non-writing artist: Where do you find original material? by John Braheny

- Songmine: For the non-writing artist: Why you need original material by John Braheny

- Songmine: Scoring Films on a Low Budget Part 6 by John Braheny

- Scoring Films on a Low Budget Part 5 by John Braheny

- Songmine: Scoring Films on a Low Budget Part 4 by John Braheny

- Songmine: Scoring Films on a Low Budget Part 3 by John Braheny

- Songmine: Scoring Films on a Low Budget Part 2: Research and Spotting

- Songmine: Scoring Films on a Low Budget Part 1

- Songmine: The Chances for Advances by John Braheny

- Songmine: What a Record Company Needs to Know – Part 6: Attorneys by John Braheny

- Songmine: What a Record Company Needs to Know – Part 5: The Professional Team by John Braheny

- Songmine: What a Record Company Needs to Know – Part 4: What Makes This Act Marketable? by John Braheny

- Songmine: What A Record Company Needs to Know : Part 3

- Songmine: What A Record Company Needs to Know: Part 2 by John Braheny

- Songmine: What A Record Company Needs to Know: Part 1 by John Braheny

- Songmine: Getting the Most from the Trades Part 4

- Songmine: Getting the Most from the Trades Part 3 by John Braheny

- Getting the Most from the Trades

- Songmine: Publishing III

- Songmine: Leave Your Ego at the Door

- Songmine: “Feedback: Why some publishers won’t give it”

- Songmine: Dealing with Rejection by John Braheny

- “Music in Print” – A Songmine Column from Music Connection Magazine March 19-April 1, 1981

About Songmine and Music Connection Magazine:

John Braheny met Eric Bettelli and Michael Dolan right before they were going to publish Music Connection magazine. Eric and Michael wanted to get their publication out to as many songwriters as they could. They had already heard of the LA Songwriters Showcase, and of John and his partner, Len Chandler. John’s goal was to advertise the schedule of guest speakers and performers at the weekly Showcase… so they made a deal.

They published John’s Songmine column (he had never before written a magazine article!) in their very first edition, in November 1977. Trading out the column for advertising, this arrangement continued for many years. Plus, Eric and Michael came to the Showcase each week and distributed free copies to the songwriters!

Those articles became so popular that (book agent and editor) Ronny Schiff offered John’s articles to F&W Media, where they became the backbone of John’s textbook, The Craft and Business of Songwriting. As a follow-up, Dan Kimpel (author, songwriter, teacher), who had also worked at LASS, took on the Songwriting column at Music Connection magazine which continues to this day! You can subscribe to get either hard copies or online.

No comments yet.