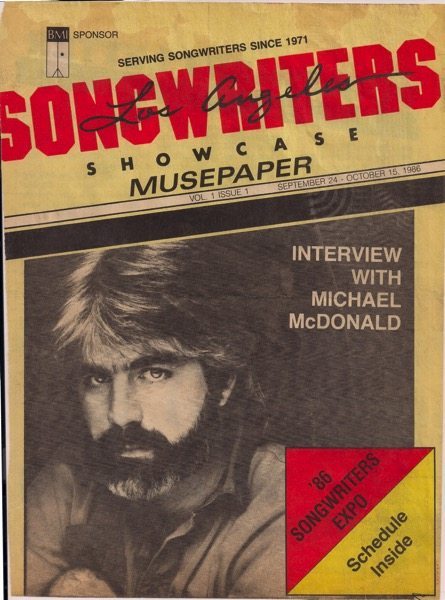

John Braheny was a diligent researcher, amassing a amazing amount of information about the music industry … not just for himself, but to provide teaching tools for songwriters/performers and others interested in how the music industry works. He loved meeting people who were pivotal in their particular roles and was eager to ‘pick their brain’ for how they did what they did. He and his partner, Len Chandler, founded The LA Songwriters Showcase and as an an ideal setting in which to conduct a ‘live interview’ on stage, with hit songwriters, singers/musicians, music publishers, managers, agents, record company executives, and more. Some of those ‘raps’ are provided here in the Archives in audio form, some in written form, and some later ones in video form. Most important to John was that the interviewee had something valuable and helpful to share. He wanted to know their ‘process.’ He later did interviews, (or led panel discussions) for the California Copyright Conference, the West Coast Songwriters Conference, TAXI Road Rally conferences, United Airlines “In-Flight” Audio Series, and many other outlets from 1971-2011. — JoAnn Braheny

An Interview with Mark Isham from The John Braheny Interviews

His Improvisational Composition Style, Embrace Of Musical Diversity And Technology, Create His Unique Edge

September 22, 1995

from the John Braheny Archive on the Craft and Business of Songwriting

Mark Isham started his performing career as a trumpet player with the Oakland and San Francisco Symphonies, segued into jazz as a member of progressive groups, Rubirosa Patrol and Group 87. In 1983 he began a solo career with the release of Vapor Drawings on Windham Hill. He recieved Grammy nominations for his Castalia (Virgin) and Tibet (Windham Hill) and a Grammy Award for Mark Isham (Virgin). Meanwhile, he contributed as a guest artist to projects with The Rolling Stones, Willie Nelson, Toots Thielemans, Robbie Robertson, Tanita Tikaram, Van Morrison, Bruce Springsteen, Kenny Loggins, XTC and many other artists.

Vapor Drawings gave him the chance to score his first film, Never Cry Wolf, followed to date by more than 40 other films including, The Net, Golden Globe nominee Nell, Losing Isaiah, Miami Rhapsody, Safe Passage, Time Cop, Quiz Show, The Getaway, Short Cuts, Made In America, Of Mice and Men, Cool World, Billy Bathgate and Little Man Tate. His score for Robert Redford’s A River Runs Through It earned him a 1993 Academy Award nomination for Best Original Score and a 1994 Grammy Award nomination for Best Instumental Composition For A Motion Picture.

Columbia has just released Isham’s new album, Blue Sun, with his quintet featuring David Goldblatt (keyboards), Steve Tavaglione (saxes), Doug Lunn (bass) and Kurt Wortman (drums). The album is an exceptional showcase of composition and musicianship. It’s melodic, visceral, subtle, minimalist, reflective with classical, ethnic and traditional jazz influences, structured but spontaneous. Everything that makes Isham unique in both his recording and film work.

JB: How did this album come together in terms of your creative process? What do you go into sessions with?

MI: Lead sheets with melody and chords, although it does vary. There are certain pieces I’ll have like a bass line in certain sections. In fact I would say most…there is a bass line into them. And it will be, “In these sections I want this exactly played this way, but then after that you can open it up, or at least in the head play this way and then improvise after that.”

Sometimes I’ll give very specific voicings to the pianist to get the mood started. “This is the way I hear this with a voice like this,” and then playing a few times that way gets the feelings in the band of a sense of what the mood of what this piece is about, and then he’s free to make it his own. I mean it is a jazz group fighting for the jazz style and I don’t expect anybody to really play it…

JB: Note for note.

MI: Yeah, but jazz composition is a fine line because if you don’t give some structure there’s no composition, and I’ve always thought, and a lot of this I’ve come to realize after twelve years of the film business, that it isn’t just the melody and the functionality of the chord. That’s the composition in jazz; the type of bass line, the type of voicing, the type of accompaniment. Sometimes it’s hard to write it down. Sometimes you just have to put some words on the page.

JB: What kind of words go on the page?

MI: Well, it’s more of a verbal description. “Let’s keep this very open. Let’s keep this…this is a dense section.” Rather than trying to write, well what will that be. “Well, I’m interested in the way you interpret the feeling of ‘let’s make this dense.’ That’s what being a jazz group is about. This is the way we’re going to interpret it.

JB: So, it’s that kind of improvisational composition as opposed to sitting down and writing out all the parts and orchestrating everything.

MI: There are certain films that I write this way for. Certain films will take an ensemble improvising the score to a degree, and then it becomes even more this way because it needs to be very specific. Film music has to be very specific. And yet if you want to keep an improvisational flavor, how do you do that without telling everybody exactly…well, what do you do, you have to direct them. You have to be a music director in a sense. “All right from bar 10 to bar 15, beat three, where the door slams I want you guys to play very chromatically and get faster and faster and faster.” And that becomes the composition – just a set of verbal instructions.

JB: So, you have to have a lot of trust in the musicians too, and an understanding ahead of time about how they’re likely to interpret it.

MI: Exactly. In hiring them I’m a casting director. Like I’ll say that in this film we need people who can really put that, say 40s jazz style together, so I’ll cast people who are either of that age, or younger guys who I know personally love that age and can emulate it very well, and say, “This where we’re at. We’re in 1943, we’re in New York. You’ve got to play like that and then, within that style, do the following thing.”

JB: Quiz Show was like that.

MI: Quiz Show was very much like that.

JB: What’s the process when you work on a film? Are you usually brought in early?

MI: Yeah, it depends. Certain directors who know me and know they want me will generally call up pretty early because of my schedule. They’ll try to book it and I’ll have a script and I may visit them on the set. The way that I see it happening most of the time is that when a director comes back from wrapping up their shooting they will have started to think about the music because the editor will be putting the rough assembly together. They might be starting to throw up some temp music against the picture to see what works. They’ll generally have an idea of whether they want the traditional orchestral, or industrial grunge music. You know, get the big decisions and start to get a direction.

My name will be on a list of maybe five people. If the director doesn’t know any of us we’ll each interview, talk, and they’ll get a sense of who they might want to work with. I’ll read a script. Sometimes they want me to see the picture if they’re confident that the cut looking good. Sometimes if they’re nervous about it they won’t show it to me. But, generally, just after the assembly is in decent enough shape for them to show it to you, they’ll make up their mind and pick you.

JB: Sometimes that doesn’t allow you a lot of time.

MI: Yeah. When I started, it used to be six to seven weeks and in twelve to thirteen years I’ve been doing this it’s come down. The consideration now is that you can do it in four to five weeks. It doesn’t make my life any easier. And for certain projects you have a lot less. Like HBO pictures and stuff. They’re usually on a tighter schedule.

JB: So, you get together with the director then to spot the film (decide where music is and isn’t needed) or just look at it?

MI: Yeah, once I’ve been chosen, yeah you look at it, you spot it, you listen to the temp score. You discuss what’s good about it, what’s bad about it, and you get to work.

JB: Then you get a video and bring it home. Do they ever re-edit it after you’ve scored it?

MI: Oh, yeah. You see in the old days, too, the idea was that you’d have six weeks with a locked picture (everything completed but the music), and I haven’t seen that in years. I’m lucky if I have two or three days with a locked picture, and more often than not they continue cutting the picture after I’m done.

JB: Then they still mess with your music after you’re finished?

MI: Yeah, then the music editor has to figure out how to make it fit.

JB: What about the communication process between a director and composer? If they’re not musically inclined and can’t tell you in musical terms what they want, what kind of a language goes on?

MI: You just have to pick it as you go with each individual, enough to get a sense of how they express themselves. You run into every balance here. You run into the director who is sure that they’re an expert in music and actually hasn’t the faintest idea of what he’s talking about. You run into the one who says, I don’t know anything about music, but actually ends up being very literate, not with the exact vocabulary of music, but in terms of emotional content, flow and dramatic structure, and every permutation in between. And, obviously, I prefer the person who just knows how to speak well about art and their concept in general and is sure in his own mind of what he’s trying to achieve and let me worry about the actual musical vocabulary.

JB: How would you describe that translation process from the visual into the emotional content? I mean, you know what the action is and what kind of a scene it is, but is that describable?

MI: Oh, yeah. I think it is. Sometimes directors aren’t good at talking about it, but I think the more intelligent and talented directors can, and certainly the more experienced directors have years of communicating this to a variety of different people from the cinematographer to the actors to the set designer.

JB: But how do you translate it into musical terms?

MI: Well, I find there are two things I have to know from the director. First of all, people in general I think get hung up in this word, emotion, and I get a lot of this thing, “it needs to be more emotional.” Well, emotion is just a very general word which describes a wide variety of different feelings and expressions, so the first thing to do is to get them to be more specific. “When you say more emotional, do you mean more quantity of what? Is it grief we’re talking about, or is she actually apathetic. Is she past grief? Or, is she coming out of grief and maybe getting a bit angry?” And to really understand the various tones of emotion that exist in the human experience, and then my little trick, of course, is to know what musical ideas express each one and then in the scene, to understand the structure of the scene. “What is the turning point here. Where is the point where this character realizes he’s in love, or realizes she’s a bad girl, or realizes his son is dead.” So you know where the turning points are. I have to go from here to there. By then the character already knows it. Here’s the point, as he goes through the door, so that you can put your bookmarks out there, and then know exactly well, all right…and up until this point he’s just totally apathetic. He doesn’t give a shit. But at this point he sees a glimmer of hope and his emotion turns. And a good director knows that because he got his actors and he got all his people to go for all those things, and you just have to duplicate that with your language. And whether that means running a counterpoint against it, or whatever device you come up with, it comes from understanding the structure of the scene. And in action films, it’s the same way. Up until then he’s the antagonist. Now he’s being chased. Now he’s scared because he’s running away, so just finding the structure is critical.

JB: Do you do a quick sketch as you’re listening in terms of finding your themes? Do you start that at the time you get a script?

MI: Well, you see when I started writing in the early ‘70s it was pre popular use of electronics, so before I could even afford a piano I bought an old Fender Rhodes, and I would just have a sheet of music and a pencil on my Fender Rhodes and the film. That’s how I wrote, but I was always very interested in electronics and I was sort of always saving up my money to get into the electronic game, whether it be multitrack tape recorders, or 4-track cassettes, or whatever.

I saved up and bought my first little synthesizer and I quickly discovered that even for jazz I liked mocking it up, hearing it as much as I could. I got a sense of that from owning a Fender Rhodes, you know. That gave you a slightly different sound than just the piano.

JB: Yeah, it’s got a great sustain.

MI: Yeah, and you could put vibrato on it at times and get it spooky, and so I was sort of immediately hooked by composition through technology, and I never really learned the grand classic compositional technique, of being able to sit at a large oak table with a pencil sharpener and reams of paper and just write it out. I’ve never learned to really do that.

JB: Do you think that has to do with the fact that you started out as a player, and that your music was about experiencing the music rather than thinking it?

MI: Yes, because not only was I a player but I was an improviser, and so for me improvisation and composition are almost one and the same. And in a sense my compositional process is simply one of finding any way of capturing an improvisation, so I don’t lose it and then being able to mold it into something worth hanging on to because, in a sense, that’s what composition is. You want to be able to create. I personally think there’s a big difference between thinking about something and creating it, and if you think about it, I think that’s a waste of time if you get sort of all mental about it. Real creativity I think happens way above the level of the brain and thinking and you know, computing. Creativity is creativity. It’s instantaneous and it just is.

JB: Yes, assuming you have the tools to make that real.

MI: Well, the trick is in taking it out of that little universe of which it is instantaneous and bringing it into the real world, and that’s why I say pencil and paper is so bloody slow to do that, and the technique one has to develop then is to be able to basically remember those ideas in some concrete form so you can get them down. Well, technology, affords us this great ability to either just keep the tape machine running or keep the sequencer running, and you actually have a record of at least the body performing these ideas.

JB: So, does that process work in the composing and recording of your own albums? With the group, once you’ve got a sketch of what you want, do you just record a lot of takes and then pick the best take?

MI: Yeah. For Blue Sun, we recorded like 104 minutes of music and that’s just the good takes of each song and we probably have four or five takes of each one of those songs, and we cut that down to the 60 minutes/8 tunes that are on the record. I overwrote and we over-recorded and I just picked the best of the best.

JB: So, that’s basically the same process of just going in and from improvisation, it gets right. Do you ever cut and paste or is that too artificial?

MI: No, no, I have nothing against that. I personally think that records are a medium unto themselves and should be looked at that way.

JB: And the finished product is what you offer the world, so it doesn’t matter how you get it.

MI: Yeah. I mean live records are great if you realize that this is a document of a live performance, but face it, a lot of live records go on and on, which at the time, if you’re in the third row is probably the most fantastic experience of your life. I mean I’ve had those and I’ve later matched the dates and said, “I was there that night! Let me buy that.” And you realize it’s a very different experience. Who really sits down and listens to a record anyway, I mean I try, but boy, records fulfill another function. They end up being part of other experiences in your day. And consequently I think it’s very valid to look at what that music on a record is that should be structured to really enhance its ability to communicate in that medium.

I really worked on Blue Sun very specifically in that regard to make a concise record. The great jazz records to me have a certain concept. There are obvious exceptions. Certain John Coltrane records where he plays a fifteen minute solo and it’s still fantastic, but let’s face it, he’s one of the few geniuses that come along. Three times in a century that you can actually do that sort of thing. I mean the great jazz records to me are the ones where there’s a concept there. Like Kind of Blue, and I don’t think Miles thought about this when he did this record. He just happened to be where they ended up, but I can look at it and do a little thinking about it and a little observing and learn from it, and know, that record is truly great and one of the reasons is because it’s concise, and it’s simple and it’s clear and it really just gives you, with the least amount of information, the greatest amount of communication. And if you can sort of emulate that, I think it would do you good. And I think it really did us good as a band to think about that in making this record.

The other thing that I really learned from looking at the great jazz records that I admire, they’re all band records. They’re records of guys who’ve been on the road with each other for years. They have that immediate chemistry, interactive communication with each other as a band. The great Miles Davis bands, the great Coltrane quartet, I mean the list is endless. The really great moments of jazz are made by long-term committed band relationships.

JB: You’ve been working with these guys for quite a while.

MI: That’s it. That’s one of the reasons I wanted to make this record this way with this group, because I said we’re starting to create that. We’ve been working in L.A. for over two years…well the quartet is over four years – with the saxophone player about two years, and we’ve got a thing going. Let’s take advantage of this. Let’s document and use this chemistry we’ve developed to really enhance the music and make it strong.

JB: So, the process…

MI: Yes, the process was I wrote a bunch of material, got as much of it down on paper as I thought they needed to know to get the structure, and just started feeding it at soundchecks like one or two in a soundcheck, until we’d played it a little bit, and then went in for like a real three-day rehearsal and brought in a few new pieces and really worked out all the kinks of the structure and everything. Then did two shows playing just the new material, then went back in for another two days. I amended some compositions, cleaned a few things up, and then went in and made the record.

JB: Did you pre-demo the songs?

MI: There were tapes. I made demos of compositions, because, even jazz stuff, I wrote in the computer just so I could hear it. I didn’t take a lot of time making them, but it was the sort of thing where I played the piano voices that I wanted. I played the bass line so the rhythm section could just get a sense of the vibe. And then it’s to be discarded within moments once it starts – it’s a springboard. Whereas in film music it’s very different. One of the great reasons for being a technological composer is that you’re halfway or 80% of the way towards a pretty good sounding demo just by writing the piece. You know, I’ve got my string patch, or I’ve got my piano patch, I’ve got my percussion patch, and I’m writing away…

JB: And you can play it…

MI: …I play it back for myself just to see if it’s working, obviously. It’s part of the compositional process. Well, with a few fine tunings here and there, if you clean up some and dah, dah, dah, dah, the director can hear it and know what the hell he’s going to get, which is essential.

JB: I think that’s probably one of the big differences for directors between counting on someone to write it all out and orchestrate, and they finally hear it at the session, and say, oh wow, that’s not what I wanted!

MI: I can’t imagine the nightmare. The guys that came up in that tradition where all they could do was sort of play the theme on the piano and then had to wait for the day when they got a hundred people in the room, and the director kind of goes, “That’s not really what I had in mind.” Oh, man!

JB: Yeah. Wasted a lot of money.

MI: I’ll do anything to avoid that, I mean I’ll demo for the whole five weeks, and I do. I insist the director take a moment and listen to it, and 99.9% of the time they’re more than happy to come out here and sit down and go through it. “Try it without the drums, try it with the drums” and they get into it. It’s fun.

JB: So, at what point do you start sketching out themes? Is that kind of an improvisation to the screen?

MI: Yeah, I mean for me it is, although you sort of have to develop certain techniques to get to it quicker than just free-form improvisation. My first choice on film composing is to pick a vocabulary. I mean here in the end of the 20th century, the musical vocabulary that a composer has to draw from is infinite. Not only do we have access to the entire global culture – the media, the medium and the transmission of digital information, you could hear African drummers, you could hear Findlandish ice dancing and you can get anything you want and check it out for inspiration. You have the whole world of processing of sound from the Moog synthesizer up to sampling to Sound Design.

I think one has to really say that the sound palette is infinite, so it’s very important that you pick the area in which you can work, because if you don’t you get this sort of hodge-podgy feeling, and one of the most successful things for me that really contributes to the success of the scores is to pick a musical personality and cast that score, and find the vocabulary here that’s really going to reflect this film, the characters in the story. Not to say that you can’t amend it as you go on, or even switch in midstream if you’ve made the wrong choices, but for me it’s essential to pick the sound of the film.

JB: By way of the instrumentation and, are keys important?

MI: Key becomes an issue slightly down the road from there because you are also obviously picking sounds that are going to reflect a certain general tone. Like I’m working on a film right now which is very, very dark – about death row. Well, you don’t want heroic French horns. You know the sounds you pick have to reflect the world – the world of the jail, of isolation, loneliness, the whole thing. That’s really where I start, especially because I write with sounds. I get the sounds up, I push a key and I hear them, and that’s how I get going so it’s important for me to pick what I’m going to start with, and that can mean either just getting out the “fake orchestra” that I’ve developed up to this point. I’m always trying to get my fake orchestra to sound better and better as the technology develops. Whether it means getting that out because I’ve decided it ‘s going to be an orchestral score or whether it means I’m just going to use strings, but I want a certain type of synthesizer backdrop in here that’s very cold, and spending a day or two programming some few things. Picking the few types of synthesizers that get that sound, or calling up somebody and saying, “Look, could you help me out on this. Can you give me a card from the Wave Station that has a bunch of cold sounds.” Give them the right words, get people to contribute in that regard, and then you sit down and start going. Because for me, if I’m looking at a scene can I just hold one note of a certain sound against the picture and know if that sound is helping that scene, or fighting the scene. You just have to hold one or two notes against it, and say, “That’s right. There’s a relationship here.”

JB: So, you start with your sounds then you get into themes if it needs it?

MI: Yeah, and the theme, I’ve experienced probably the two far ends of the spectrum. I’ve experienced sitting down and being able to have written the theme day one, the right theme. It happened on A River Runs Through It, although we didn’t think so. Bob (Redford) said, “Well I’m not quite sure,” so I changed it a few times. And he said, “Why don’t you try something else.” And I tried something else, and we came back to the first thing I’d written on day one. And he called back and said, “You know Mark, I think I’ve really led you astray. That first one was mighty good.”

I’ve worked on other pictures where it’s just like, I don’t have a theme. We recorded four days, I don’t have a theme. I’ve got lots of cues – I’ve lots of sort of little motifs, I’m hinting at something, but I can’t find the full 24 bars, or the full 18, or whatever that exposition of the whole idea is, and at the last minute I find it. And then it’s a mad scuffle to make sure it’s attached in all the right places. So, I can’t predict. You just have to keep plugging away and hope for the best.

JB: Do you have it worked out as to how much time you usually spend on a minutes worth of music, because I assume there are times when you have to predict how much time it’s going to take you to finish?

MI: It varies, you know. The Net had the most minutes of music that I’d ever done before, somewhere between 90 and 100 minutes to final take. I had less than five weeks, so I was constantly adding up my minute-per-day ratio so I get done in time and if I have to stay until five in the morning to get my minute limit per day done, then that’s what I have to do. And if you slip behind then that ratio goes up. JB: Did you find when you started working in film, that it influenced, in any way, the the non-film music that you do?

MI: In writing outside of film I find it refreshing not to have to be tied to specific images, that I like letting the music be the creator of the image. That’s one of the real reasons that I like the several differences of a solo career. One is that the music leads the whole creative process as opposed to film leading the creative process, that I lead the process as opposed to a director. I’m a member of his team. It’s a different flow, both as just a person and then for the music itself. The music is different because it is the leader and I just appreciate being the creative leader. That’s very important for me, and I think if I were just in the film business for the rest of my life I’d get a little bent, perhaps, by just being stuck in that one type of creative relationship where I’m always fitting myself into some other vision, and the fact that I do move out and have an area where I can work that is my vision. The music can take the lead, and then it allows me to go back into the film business with a very positive attitude towards doing it because I’ve done the other.

It has to be the sanest thing a film composer can do. I think John Williams is very smart for doing his conducting roles and writing his own music for the records, Elfman and the other guys who do that, I think it really is the sanest thing you can do.

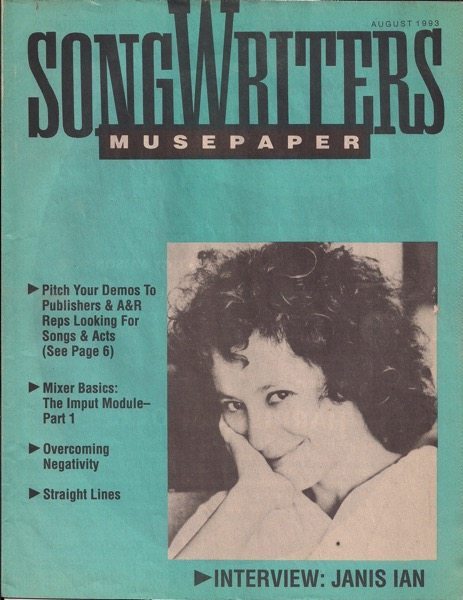

Originally appeared in The Songwriter’s Musepaper, a publication of the National Academy of Songwriters in Los Angeles, CA

***

![Archive Highlight: John Braheny speaks on The Craft and Business of Songwriting [Audio]](http://johnbraheny.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2015/11/jb-M000000102-001.jpg)